Martha Gellhorn wanted to be remembered as a novelist. Yet, most people remember her as one of the great war correspondents and for something that infuriated her, her brief marriage to Ernest Hemingway during the Second World War. Although Hemmingway was the unnamed “other” in her second chapter, “Mr. Ma’s Tigers,” when Martha was in China reporting on the Sino-Japanese war. She refused to be a footnote in someone else’s life, nor should she be. Since her death, several biographies and a significant PBS segment about her have been produced.

I became aware of her writing while researching the iconic travel writer Moritz Thomsen since Gellhorn wrote an obituary about him in which she revealed her love of “Living Poor.” She was “electrified by the absolute honesty of the man and then found “saddest pleasure,” which was Thomsen’s take on the most horrendous travel experiences that “opened my eyes.”

I found no evidence that the two authors influenced one another, although they were both fascinated with the power of what Gellhorn referred to as her “horror journeys” because “The only aspect of our travels that is a guarantee to hold an audience is disaster….” She says, “The fact is, we cherish our disasters, and here we are one up on the great travelers who have every impressive qualification for the job but lack jokes….”

She reveals the inspiration for this book in the first paragraph of her text:

I was seized by the idea of this book while sitting on a rotten little beach at the western tip of Crete, flanked by a waterlogged shoe and a rusted potty. Around me, the litter of our species. I had the depressing feeling that I spent my life doing this sort of thing and might well end my day here. This is the traveler’s deep dark night of the soul and can happen anywhere at any hour.

Gellhorn was in her 50s when she made her “horror journeys” but didn’t write the book until twenty years later. Most of her travels occur in Africa. In the early 1960s, she made some money after selling a short story for TV and decided to travel for fun, although she doesn’t mention that she left her adopted son behind.

Her travels took her to the Caribbean in 1942 after she learned that two hundred and fifty-one merchant ships were sunk in the Caribbean alone. The author loved journalism and the chance to see and learn something new.

This journey tells of her experiences “Messing About In Boats,” where she was “…Soaked to the skin, frozen, nauseated, I swore that I would never travel by sea again after I reached Antigua. Sea was for swimming, wonderful for swimming. Otherwise, I loathed it.” She also revealed an essential component of horror journeys, “…once you are on them, you cannot change your mind and get off them.”

Most of her African horror stories are from West Africa, where I spent three years in Sierra Leone and could identify with some of her challenges and nuances. She starts in Cameroon and Chad, which don’t impress her. Once she arrives in Nairobi, Kenya, she refuses to join an organized safari and insists on renting a Land Rover and exploring independently. Although typical of the early 1960s, the British safari guide refused to rent her a car unless she had a chosen companion to “protect” her.

One of the most significant challenges of Gellhorn’s travels in Africa is caused by the sense of smell, and she states that she never realized that the “…nose could be the greatest barrier to human brotherhood.” She goes on to say:

I’m nauseated by the smell of the blacks, unique in my experience—a sweetish stink of mixed urine and sweat—and very ashamed of myself. Cannot overcome this by act of will. No feeling about colour at all; on the contrary, the people who look right here are the blacks, the people that look out of place and queer are the whites. I think I cannot become friends with anyone whose mind I cannot reach…and am driven off by the horror of smelling them. This is going to be a nice problem.

As she travels deeper into Africa on her safari, she says it feels “oppressive.” She also describes the incessant sound of drums in the background, which reminded me of nights spent upcountry in Sierra Leone, “The drumbeat is monotonous and untiring and merges finally with the steady grinding of the insects. The trumpets sound like reedy flutes and make music like that of Indian snake charmers, but the tune is always the same. In the dining room, the gramophone plays a record of a French crooner.”

She concludes, “I feel that man is a brief event on this continent; no place has ever felt older to me, less touched or affected by the human race. But the blacks and the wild animals belong here…No one else does; and I doubt if civilization, our kind, ever will.”

The author didn’t like Uganda, which was preparing for independence.

“…The predicted bad trouble; without Europeans to oversee and direct, the economy would go to hell; kiss the coffee and cotton exports goodbye; the idea that Ugandans could govern themselves was madness. She says, “Africa is too big, everything in Africa is too big. People were never meant to live here. It should have been left to the animals. They came first. It’s their place.”

Some of the author’s wit and humor emerge when describing Joshua’s traveling companion, who the British safari leader chose. After touring with him for weeks she reveals what she’d learned about him,

“…I knew that Joshua was a hundred percent city boy, with very weak nerves. I still didn’t know if he could drive. He knew that when I was tired I was as lovable as a rattlesnake, and I had been increasingly tired every day. Not what you’d call a true meeting of minds. The hell with it. It was over and the next time I chose to circumnavigate the globe, I would be more careful in selecting my companion. For a start, I would ask him to drive round the block.”

A month after her return home to London, Joshua wrote her on fine paper saying that he would never forget our safari, he had never been so happy in his life, and I was his mother and father.

Her “love affair” with Africa was long, obsessed, and unrequited, lasting thirteen years. “Africa remained out of reach except for moments of union, when walking on the long empty beach at sunrise or sunset, when watching the night sky. Or later when I had built my two-room tenth permanent residence high in the Rift Valley and could look at four horizons, drunk on space and drunk on silence. Or always, driving alone on the backroads, when Africa offered me as a gift its surprises, the beautiful straying animals, the shape of the mountains, wildflowers…”

As a travel writer, I found her “Non-Conclusion” especially interesting:

Amateur travel always used to be a pastime for the privileged; now, it is a pastime for everyone. Perhaps the greatest social change since the Second World War is the way citizens of the free nations travel as never before in history. We have become a vast floating population and an industry; we are essential to many national economies, not that we are therefore treated with loving gratitude, more as if we were gold-bearing locusts… Americans overload their own National Parks and resorts, fly by millions to Europe, and inundate Mexico. Are we having the time of our lives?

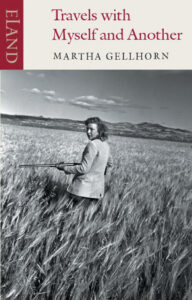

I received my copy of this book from the editor of ELAND Press in appreciation of my article, “My Saddest Pleasures,” about Moritz Thomsen. When the founder of ELAND books, John Hatt, was asked about the possible connection between Gellhorn and Thomsen, he said he didn’t know of one, but he remembers going “gaga” over Martha. ELAND first published this book in 1982 and reprinted it again in 2007, thus confirming their mantra, “Keeping the Best of Travel Writing Alive.” And I must agree with the ELAND publicists who remarked that Gellhorn is a “…woman who makes you laugh with her at life while thanking God that you are not with her.”

Martha Gellhorn (1908-98) published five novels, fourteen novellas, and two collections of short stories. This was her best travel novel. As a war correspondent, she covered most major conflicts over sixty years, from the Spanish Civil War to the American invasion of Panama in 1989. The Martha Gellhorn Prize for Journalism is named after her.

Her letter to Tom Miller in April 1995 explained that she couldn’t review the book he’d sent since her eyesight was destroyed in 1992 by “a famous Harkey Street twerp during a routine cataract operation.” This would culminate in her apparent suicide in 1998 when at 89, suffering from ovarian cancer, which had spread to her liver, and almost totally blind, she apparently committed suicide by swallowing a cyanide capsule.

Mark Walker was a Peace Corps Volunteer in Guatemala and spent over forty years helping disadvantaged people in the developing world. He’s worked with groups like CARE and MAP International, Food for the Hungry, Make-A-Wish International, and was the CEO of Hagar USA.

His book, Different Latitudes: My Life in the Peace Corps and Beyond, was recognized by the Arizona Literary Association. According to the Midwest Review, “…is more than just another travel memoir. It is an engaged and engaging story of one man’s physical and spiritual journey of self-discovery.”

His articles have been published in Ragazine and WorldView Magazines, Literary Yard, Scarlet Leaf Review, and Quail BELL. At the same time, the Solas Literary Award recognized two essays, including a Bronze award, in this year’s “Best Travel Writing” adventure travel category. Two of his essays were winners at the Arizona Authors Association Literary Competition, and another was recently published in ELAND Press’s newsletter. He’s a contributing writer for “Revue Magazine” and the “Literary Traveler.” His column, “The Million Mile Walker Review: What We’re Reading and Why,” is part of the Arizona Authors Association newsletter. He’s working on his next book, Moritz Thomsen, The Best American Travel Writer No One’s Heard Of. He continues to produce a documentary on indigenous rights and out-migration from Guatemala, “Trouble in the Highlands.” His wife and three children were born in Guatemala. You can learn more at www.MillionMileWalker.com.