I first became aware of the author when she made a presentation at the Phoenix Writers Network. I had an opportunity to share some similarities in our experiences, since Guatemala and Bolivia have a high percentage of the Indigenous population. I learned that she was from a Native American community, which gave her a perspective most volunteers couldn’t understand or appreciate. Like many volunteers, I was focused on just learning Spanish and surviving, so I wasn’t prepared to learn one of the 22 Mayan languages in Guatemala.

When the author revealed that the pages of her copy of Moritz Thomsen’s book, Living Poor were “dog-eared,” I realized we had another area of common interest. I’ve written multiple articles on Thomsen and have many of the essays from fellow writers who knew and were inspired by Thomsen, which I plan to make into an anthology, Moritz Thomsen: The Best American Writer No One Knew About.

When the author began research for writing this book, she didn’t find anything examining the experience of a Native volunteer serving in an Indigenous country. “I wrote this book because the story of an American Indian Peace Corps volunteer who struggled while serving in an Indigenous country—my story was missing from the library.” And yet, Bolivia had four million Indigenous people, almost twice as many Natives as in the United States. And she learned Quechua as a volunteer.

The author is from the Karuk tribe in Oregon, which posed unique challenges, as she asked herself, “Couldn’t the Bolivians see that we shared a connection? Couldn’t they see that my commitment was more meaningful because I was Native?” The answer was no.

But the author brought many insights into the challenges of cultural assimilation for Native Americans. Her great-grandmother never went to school and spoke little English. Her grandmother learned English in school and, as a teenager, went to Arizona to the Phoenix Indian School, but spent most of her life in the Bay Area. The further away she moved from her family and culture, the more she rarely spoke Karuk. So, the author appreciated the downside of some development as Indigenous groups in Bolivia also began to lose their language and culture.

The author used her experiences of a lifetime of adapting to the rules of the dominant society in the United States, which taught her to watch and mimic how people dressed or spoke, and used that skill in Bolivia to fit in. While many of the other volunteers in her group did whatever they wanted, “making no attempt to comport themselves to reflect Bolivian norms… Maybe I was the stupid one for attempting to dress or act like the Bolivians. But it was the only way I knew how to survive…When I was around other volunteers like this, I often had the feeling of not wanting to be associated with them….”

During the initial training, the author and her group watched “Blood of the Condor” or “Yawar Mallku,” a 1969 Bolivian film about Quechua villagers and an agency called the “Progress Corps.” The training director told her group, “This movie changed the history of the Peace Corps in Bolivia.” It was totally in Quechua, and the volunteers from the U.S. spoke “laughable and barely understandable” Spanish. The film showed the worst of cultural imperialism, horrid development work, and the practice of forced sterilization, which the volunteers seemed to be unaware of. The author points out native women were forcibly sterilized, “starting with full-blooded women.”

The author showed an enviable level of transparency relating to alcohol, drugs, cheap cocaine, and the sexual norms of volunteer life. “Among the male volunteers, getting together with Bolivian women was a competition. How many parties had I attended where a gorgeous Bolivian woman arrived on the arm of some short, pale volunteer with stringy hair?… For the female volunteers, it was different. A female volunteer involved with a Bolivian man was assumed to be weak and insecure or else just passing time. But our dating options were limited….” The author tells of her relationship with a Bolivian, married man, and the isolation she often felt which eventually led to a suicide attempt.

At the end of the book, the author reveals that the Peace Corps was asked to leave, and the value of the Peace Corps was seriously questioned. The author returned to Bolivia with her husband. They were impressed that under Evo, a new constitution made the country’s thirty-seven Indigenous languages official national languages for the first time. Other changes included nationalizing foreign companies making money from gas and oil resources, which the country’s economy depended on. The author ends her book with the wish that it will open opportunities for black, Indigenous and others of color to publish their Peace Corps stories.

The author and her RPCV Bolivia husband, although they weren’t there at the same time, participated in a revealing webinar at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 2021, which is worth viewing on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4bLqoRBnGas

The Author

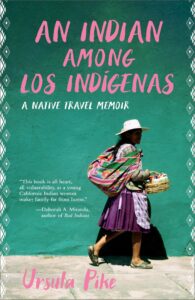

Ursula Pike lives in Austin, Texas, and writes about identity, Native American issues, economics, travel, and powwows. She graduated from the Low Rez Creative Nonfiction MFA program at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico. She is a member of the Karuk Tribe and grew up in Oregon. Her debut memoir, AN INDIAN AMONG LOS INDÍGENAS: A NATIVE TRAVEL MEMOIR, about the two years she spent in Bolivia as a Peace Corps Volunteer, was published by Heyday Books. Her work has appeared in Ligeia Magazine, Yellow Medicine Review, World Literature Today, and O’Dark 30. For more information, visit www.ursulapike.com

Product details

- ASIN : B08Q8N1WVV

- Publisher : Heyday; 1st edition (April 6, 2021)

- Publication date : April 6, 2021

- Language : English

- File size : 989 KB

- Text-to-Speech : Enabled

- Screen Reader : Supported

- Enhanced typesetting : Enabled

- X-Ray : Not Enabled

- Word Wise : Enabled

- Print length : 218 pages

The Reviewer

Mark D. Walker was a Peace Corps Volunteer in Guatemala, 1971-73, working on fertilizer and seed experiments in the highlands. He is a contributing writer at Literary Traveler and Revue Magazine. He was a Peace Corps Volunteer in Guatemala and worked with international agencies like MAP International, Hagar, and Make-A-Wish International for over forty years. Different Latitudes: My Life in the Peace Corps and Beyond was his memoir, soon followed by, My Saddest Pleasures: 50 Years on the Road. Two of his 25 articles were recognized by the Solas Literary Awards for Best Travel Writing, with a Bronze for “Travel Adventure.” His wife and three children were born in Guatemala. Over 60 book reviews and 25 articles can be found on his website, www.MillionMileWalker