Time Among the Maya: Travels in Belize, Guatemala and Mexico

by Ronald Wright

Reviewed by Mark D. Walker

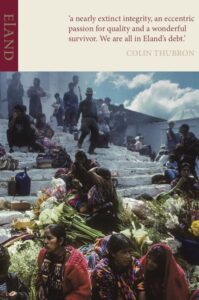

I came across this travel classic after writing an essay published in ELAND Press and as a token of appreciation, the editor offered any three of their books. Naturally, my first choice was the book with the cover of the iconic Santo Tomas church of Chichicastenango which is filled with a mix of Indigenous flowers and women in traditional garb (traje), and the smell of incense emanating from the catholic church which often has chickens being sacrificed on the top. Very appropriate for a book that covers both the lives and culture of today’s Maya culture but also the complicated culture and religious nuances. A travel book that covers both the Old and New World simultaneously.

Although I was managing programs in Sierra Leone, West Africa when the author wrote his book, I’ve traveled to many of the places he describes, including the unforgettable hotel Santa Tomas where the author and team stayed,” …There’s hot water, colonial-style furniture, even a corner fireplace and a stack of logs. The room is arranged around patios full of flowers, stone fountains, and parrots on perches…”

But he adds an important fiat which he also pursues throughout the book, “…I should be a delightful place, but now it feels tainted. According to human rights organizations, there were fifty-four massacres in El Quiche during 1982 alone; more than three thousand civilians were killed.” As is the case throughout the book, he provides the source for this disturbing reality—in this case, a report published by the “Guatemalan Church in Exile.” The author traveled through some of the hardest-hit areas such as Nebaj, and Uspantán in the Department of Quiche, areas I’d worked in and around for many years.

He begins each chapter with Maya glyphs/script and an explanation of their meaning. He also provides maps, a Glossary, Bibliography, and Further Readings—a very comprehensive presentation.

Although I’ve studied the Maya and Guatemala extensively over the years and have a degree in Latin American studies, written extensively in my book/essays, I’ve rarely found such a mix of the literary and the historic materials in this book. Here’s his description of the area surrounding the Santo Tomas hotel in Chichicastenango:

Our room looks out on the canyons and the magnificent pine-bristled hills that climb out of them and stride toward the horizon. The cloud has lifted from the western mountains, allowing the sun to throw a weak coppery light on dark trees. Bright green clearings glow on the hillside wherever a farmer has a patch of young corn…

And of a Maya shaman-priest, worshiping at a family shrine, “I notice other plumes of smoke, blue against the dirty clouds, rising from small fields higher up in the mountains. Apart from the worshipers, everything is still; one has the feeling of being in an enchanted place, a land of ancient numina.”.

The author takes the reader to Tikal, “Here on their tallest building, in their greatest metropolis, I’m at the center of the Maya world” and describes the panoramic setting as follows:

From the top, the forest stretches to the horizon on all sides, diaphanous waves of mist washing across it like an ocean swell. The dark canopy, showing through in lacy troughs, hints at bottomless green depths, and from these rises the steep islands of the five great pyramids…

The author transported me to the ruins of Iximché which I’ve visited many times outside of Tejutla on the Pan American highway, “Iximché is a tranquil park, about a mile long and up to a quarter-mile wide. Remains of temples, palace platforms, and two ballcourts stand whitely among well-mowed lawns. Stands of ocote and Caribbean pine cover what were once suburbs and the steep cliffs protecting the Cakchiquel stronghold. A raven’s croak echoes in the woods…”

The tone of the journey through the Guatemalan takes on a different tone as the author learns of the devastating period of violence in Guatemala which he witnesses firsthand as he traveled through in the early 1980s. The “Afterwards” of 2020 version published by Eland Press refers to the United Nations Truth Commission in 1999 which summed up the impact as, “…93% of civilian killings between 1961 and 1996—more than 200,000 all told—were the work of Guatemala state forces, often with the United States and other foreign support. More than four-fifths of the victims were Maya…”

Wright provides the backdrop of the circumstances which lead to this level of killing by the Kaibiles, or “Tigers” crack counterinsurgency troops modeled on the Green Berets, with this responsorial chant at a training camp:

What does a Kaibil eat?

FLESH”

What kind of flesh?

HUMAN!

What kind of flesh?

COMMUNIST…

The author quotes a report that a survivor of the July 1982 massacre at the village of San Francisco said he saw a soldier cut out the heart of a warm corpse and put it into his mouth. The real tragedy is the term Kaibiles (a Mayan, Mam leader) has been appropriated to describe a group composed basically of non-Mayan “Ladinos”. “The atrocities allegedly committed by them and other army units, are like the early accounts of Nazi horrors, strain the belief of anyone living far from the social climate in which they took place. But reports are many and detailed…”

The violence impacted all levels of Guatemalan society as well. One of the author’s stories brought back memories of my visits to the coffee plantation on the southern slopes of the Atitlan Volcano, San Francisco Miramar owned by my wife’s grandfather. The area was partially occupied by the guerrilla group ORPA, so they’d come in during the day to talk with the workers followed in the afternoon by members of the Guatemalan army. In this case, an honorary consul of Norway lost his life when his small plane landed at the neighboring Finca Panamá for a visit and was attacked by members of ORPA who thought the flight was part of a military operation. It was a wild time, and the Norwegian consul was in the wrong place and the wrong time which could happen to anyone.

I always appreciate the insights a British-born traveler like Wright brings when describing the role of the U.S. in violence. United Fruit and the U.S. government justified much of the killing due to a “communist threat,” which the author sums up as, “…The political current flows south not north. The idea that Nicaragua, El Salvador, or Guatemala might spread some ideological contagion northward through Mexico to the gringo empire is the most ludicrous paranoia, Unfortunately for Central America, the United States suffers from what Carlos Fuentes has called “unabashed historical amnesia.”

What impressed me the most about this book was the author’s ability to pinpoint some of the key issues which impacted the countries he visited in the 1980s and continue to influence the situation in Central America today. He points out that Guatemala, like most countries in Latin America, has a paper country and a real one. Guatemala has the paper Guatemala—constitution, as a system of justice and regular free elections while the “real” Guatemala is,” …selfish interests seize power and hold it by corruption and terror.” The two countries pull in opposite directions—the one belongs to the military regime the other to insurgents; one is urban, the other rural; one depends on infrastructure—roads, airstrips, open fields- the other thrive in the wilderness. This is not a new pattern: it has been the fundamental structure of the Guatemalan conquest-state since 1524.”

The author calls “Ladinoization” a process brought about by overt racism and persecution. The Ladinos use European attire and speak Spanish and determining the percentage of the population which is still Mayan is complicated because under certain circumstances they become Ladinos. “In Guatemala, as in other Latin American countries, “race” is more a matter of culture than genetics: one is an Indian because one defines oneself as such by wearing the clothes, speaking the language, and keeping to the values and traditions that symbolize Indian ethnicity.”

The role of epidemics in bringing down much of the Indigenous community was breathtaking, “…between 1520 and 1600 their populations fell by about 90 percent. At least 40 or 50 million people must have died…” It was the greatest demographic collapse in human history: proportionally three times more severe than the Black Death, which severely disrupted late medieval Europe without an accompanying invasion. “Great was the stench of the dead,” recalled the Annals of the Cakchiquels.” The plague referred two was probably smallpox.

Another insight into the life of the Maya was that their greatest strength and greatest weakness was their disunity. “They could not be subdued like the Aztecs by the destruction of a single city, nor paralyzed like the Incas y the ransom of a god-king. But their internecine squabbles blinded them to the Spanish threat until it was too late.”

This diversity is reflected in the 23 different languages the Maya speak. The author illustrates this with a language chart of basic, traditional words in each language. The words of the Ixil and Quiche (which are in the same area) are very different from the Yucatec language of the Mayan in the Yucatan. This contrasts with the legacy of the Inca Empire of Quechua and the state bilingualism the Bolivians have. “So, the Maya has been condemned by history to the margins of the modern world. But, like the Welsh, the Maya do not give up their culture easily.”

The complex world of religion among the Mayas is adeptly illustrated through the image of the church off the shores of Lake Atitlan in Santiago which was built in 1568 and “…is full of ancient and bizarre wooden saints propped against the walls. They are not static or serene, but stooping, writhing, dancing, oozing a glutinous blend of sanity and pain.” These “saints” are cared for by a Maya organization called cofradías or “brotherhoods” which have been the framework of local government as well. To the Catholic hierarchy, this practice was a form of ancestor worship and the most important one was “Maximón.” According to the author, new Catholics said he was an” effigy of Judas Iscariot”. But experts say his name meant San Simón mixed up with max, a Maya word for tobacco. (The Maximo I visited in Santiago appeared with a big cigar between his wooden lips—just like the ancient Death Lords) and his followers bestow him with many meanings and roles.

Wright recognizes the complexity and danger he encountered on his trip with a comment he makes when departing, “At midnight I walk across the international bridge. A small boy changes the last of my quetzals for pesos. Mexico! Suddenly I realize I’ve been holding my breath for weeks.”

In the “Epilogue” he states, “The modern Maya are traveling many roads: the hard road of armed resistance, the silent road of refuge; the seductive road of accommodation…On my journey, I have not found what I feared: that the Maya face extinction—much more than the rest of us. If there is to be the twenty-first century, the Maya will be part of it…”

Through all the complexity the author encountered during his trek through Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize, he identified with the conundrum expressed by Gabriel García Márquez who said that Latin American writer’s great problem is not to create fantasy from what is real, “but to make Latin America’s reality believable—a much more difficult task” which Ronald Wright has done admirably. And I agree with Jan Morris of “The Independent London,” who says, Time Among the Maya shows Wright to be far more than a mere storyteller or descriptive writer. He is a historical philosopher with a profound understanding of other cultures.”

Product details

- Publisher : Grove Press; 1st Grove Press ed edition (September 30, 2000)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 464 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0802137288

- ISBN-13 : 978-0802137289

- Item Weight : 21 pounds

- Dimensions : 6 x 1.25 x 8.25 inches

- Best Sellers Rank: #1,234,839 in Books (See Top 100 in Books)

- #16 in Belize History

- #88 in Guatemala History

- #248 in Mayan History (Books)

- Customer Reviews:

4.1 out of 5 stars 24 ratings

Time Among the Maya: Travels in Belize, Guatemala and Mexico

ISBN: 978-1-78060-158-8

Format: 440pp demi pb

Place: Belize, Guatemala, Mexico

The Author

Ronald Wright is the author of ten books of fiction, history, essays, and travel published in eighteen languages and more than forty countries. His first novel, A Scientific Romance, won Britain’s David Higham Prize for Fiction and was chosen as a book of the year by the Sunday Times and the New York Times. Wright’s CBC Massey Lectures, A Short History of Progress, won the Libris Award for Nonfiction Book of the Year and inspired Martin Scorsese’s 2011 documentary film Surviving Progress. His other bestsellers include Time Among the Maya and Stolen Continents, chosen as a book of the year by the Independent and the Sunday Times. His latest work is The Gold Eaters, a novel set during the Spanish invasion of the Inca Empire. Born in England to British and Canadian parents, Wright lives on Canada’s west coast.

The Reviewer

Mark Walker was a Peace Corps Volunteer in Guatemala and spent over forty years helping disadvantaged people in the developing world with various international agencies.

His book, Different Latitudes: My Life in the Peace Corps and Beyond, was according to the Midwest Review, “… more than just another travel memoir. It is an engaged and engaging story of one man’s physical and spiritual journey of self-discovery.”

Several of his articles have been published in Ragazine and WorldView Magazines, Literary Yard, Scarlet Leaf Review, and Quail BELL, while another was recognized by the “Solas Literary Award for Best Travel Writing.” He’s a contributing writer for “Revue Magazine” and the “Literary Traveler.” He has a column in the Arizona Authors Association newsletter.

His honors include the “Service Above Self” award from Rotary International. He’s a board member of “Advance Guatemala.” His wife and three children were born in Guatemala. You can learn more at www.MillionMileWalker.com and follow him on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/millionmilewalker/