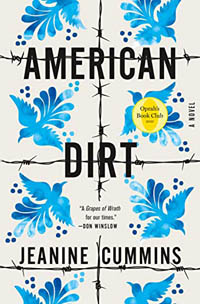

American Dirt

By Jeanine Cummins

Reviewed by Mark D. Walker

As someone who has traveled through and around Mexico multiple times, I was attracted to this number one blockbuster for Hispanic Literature. Recently, I reviewed Paul Theroux’s, “On the Plain of Snakes: A Mexican Journey,” and that, plus the brutal murder of the defenseless Mormon family by the cartel in the northern state of Sonora made this a must read for me.

As someone who has traveled through and around Mexico multiple times, I was attracted to this number one blockbuster for Hispanic Literature. Recently, I reviewed Paul Theroux’s, “On the Plain of Snakes: A Mexican Journey,” and that, plus the brutal murder of the defenseless Mormon family by the cartel in the northern state of Sonora made this a must read for me.

The story begins in Acapulco, which was one of Mexico’s key resort centers, although over the years it has become increasingly violent. Lydia owns a bookstore there and she has a son, Luca, and a husband, Sebastian, who is a journalist. Mexico also has one of the highest murder rates of journalists in the world, so the setting had potential for a true cartel-oriented disaster. According to the author, being a journalist is “….no safer than an active war zone. No safer even than Syria and Iraq. Journalists were being murdered in cities all across the country. Tijuana, Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua…”

Lydia experiences bliss stocking her all-time favorite books until she meets and develops a relationship with a charming erudite customer who happens to be the “jefe” of a new drug cartel, and when her husband writes a detailed and not very complimentary profile of Javier, their lives are changed forever. Personally, I found the depiction of the “jefe” as a literary poet questionable, but it tied all the key characters together in an interesting way.

For those who want a more hard-core, realistic depiction of the “sicario,” I recommend, “He was One of Mexico’s Deadliest Assassins: Then He Turned on His Cartel,” by Azam Ahmed and Paulina Villegas in the February 28th edition of the New York Times. In this case, the assassin said, “They took away everything left in me that was human and made me a monster.”

After the cartel murders her husband and most of their family, both Lydia and Luca are traumatized as reflected in this passage, “She will list them and repeat them and remember. Sebastian, Temi, Alex, Yenifer, Adrian, Paula, Arturo, Estefani, Nico, Joaquin, Diana, Vicente, Rafael, Lucia, and Rafaelito. Mama. Repeat….Lydia will not stop saying their names.”

One might ask why she didn’t purchase airline tickets and take Luca to Canada, but then we would have missed the transformation from a middle class family into migrants riding the infamous, and very dangerous, “Bestia” to the U.S. (Also, she was afraid of being intercepted by members of the Cartel who were looking for her). And, of course, one must wonder—what are they running to?

One compelling scene on the Bestia, when they meet up with some fellow migrants, depicts the circumstances of the journey as well as the nebulous destination, “Whatever happens, no one else in their lives will ever fully comprehend the ordeal of this pilgrimage, the characters they’ve met, the fear that travels with them, the grief and fatigue that eats at them. Their collective determination to keep pressing north. It solders them together, so they feel like an “almost family” now…Lydia closes the ugliest box in her mind, and instead allows herself to think forward to Estados Unidos. Instead of Denver, she thinks of a little white house in the desert with thick adobe walls. She’s seen pictures of Arizona: cacti and lizards, the ruddy red landscape and hot blue sky. She pictures Luca with a clean backpack and a haircut, getting on a big yellow school bus and waving at her from the window. And then she conjures a third bedroom in that house for the sisters…”

Maureen Corrigan of NPR sums up what most impressed me about this literary novel, “… its narrative hurtles forward with the intensity of a suspense tale … American Dirt’s most profound achievement, though, is something I never could’ve been told about nor anticipated. Of all the ‘What if?’ novels I’ve read in recent years—many of them dystopian—American Dirt is the novel that, for me, nails what it’s like to live in this age of anxiety, where it feels like anything can happen, at any moment. Cummins’ novel brings to life the ordeal of individual migrants, who risk everything to try to cross into the U.S. But, in its largest ambitions, the novel also captures what it’s like to have the familiar order of things fall away and the rapidity with which we humans, for better or worse, acclimatize ourselves to the abnormal. Propulsive and affecting, American Dirt compels readers to recognize that we’re all but a step or two away from ‘join[ing] the procession.’

Yet, at least as fascinating as the book itself has been, the polemic that broke out around this novel after Oprah selected it for her “Book Club.” Although the author considers herself a “bridge” between some of the brutalities of Mexican society and the reader, she has been accused of “peddling the very same racism and stereotypes she is claiming to deride.” And according to Concepcion de Leon of the New York Times, “After a scathing review by the writer Myriam Gurba, who said it relied on racist stereotypes, other Latinx writers and community members expressed similar criticism. And although the novel became a best seller, its publisher, Flatiron Books, canceled a planned book tour and more than 100 writers signed an open letter asking Winfrey to reconsider her pick.”

One Latino author in the article claimed that writers of color are expected to write only about issues such as race and immigration, while white writers have much more liberty. Others would go on to say that Ms. Cummins was not “Latino” enough (although her grandparents are from Puerto Rico). And on more than one occasion, I’ve heard the criticism that the author is taking the space of “legitimate” Latino authors.

As someone who writes about people from around the world, my feeling is that I’ve seen a lot of things most people don’t. In the case of Guatemala, for example, I’ve probably seen more isolated places than over 90% of the population, including many places most Guatemalans wouldn’t want or couldn’t get to. So, should I wait for a local author to tell my story? In most cases, I try to tell the stories told me from the locals I meet along the way.

When Paul Theroux tells about the free writing courses he offered in Mexico City to some excellent local authors, he didn’t just tell them how to write, but recommended that they act like a “Peace Corps Volunteer” and get out into the rural areas where most of the poorest, most isolated people make a living, and stay with them and listen to their stories. I’m amazed at how few books written in Latin America and other parts of the world, focus on the culture and reality of the most downtrodden and isolated groups within a population—they’re just not represented in many country’s’ literature.

In regard to getting published, writing does not include citizenship requirements. Authors must identify the publications that are most apt to consider their work. The latest “Poets & Writers” has an article, “A Prize for New Immigrant Writing,” which is the focus of an independent publisher, Restless Books. I do my research and avoid the growing number of publications that are focused specifically on “diversity” in regard to gender, race and sexual orientation, among other things. Still, I’m turned down way too often than I should be, from my perspective, but that’s life in the literary publishing world, and good writing is the great equalizer, to a degree.

And yet, possibly the greatest dilemma represented by this novel is the growing impact that advances and publicity campaigns have on the success of a book. In this case, the author received an advance of some $600,000. Then you have the marketing power of Flatiron Books, a division of Macmillan, making the publishing field less than even.

Despite its flaws and the issues this novel raises, New York Times bestselling author of “The Border,” Don Winslow, considers it the ‘Grapes of Wrath’ of our times”. Ms. Cummins has introduced many readers to the human element behind the existing immigration crisis and helped them accept their humanity, which deserves the public’s compassion and understanding.

Product details

⦁ File Size: 4878 KB

⦁ Print Length: 387 pages

⦁ Publisher: Flatiron Books (January 21, 2020)

⦁ Publication Date: January 21, 2020

⦁ Sold by: Macmillan

⦁ Language: English

⦁ ASIN: B07QQLCZY1

⦁ Amazon Best Sellers Rank: #28 Paid in Kindle Store (⦁ See Top 100 Paid in Kindle Store)

⦁ #1 in ⦁ Hispanic American Literature ⦁ &⦁ Fiction

⦁ #2 in ⦁ Psychological Fiction (Books)

⦁ #1 in ⦁ Hispanic American Literature

Reviewer Mark Walker was a Peace Corps Volunteer in Guatemala and spent over forty years helping disadvantaged people in the developing world. He came to Phoenix as a Senior Director for Food for the Hungry, worked with other groups like Make-A-Wish International and was the CEO of Hagar USA, a Christian-based organization that supports survivors of human trafficking. He’s presently the Producer of a documentary film, “Guatemala: Trouble in the Highlands.”

His book, Different Latitudes: My Life in the Peace Corps and Beyond, was recognized by the Arizona Literary Association for Non-Fiction and, according to the Midwest Review, “…is more than just another travel memoir. It is an engaged and engaging story of one man’s physical and spiritual journey of self-discovery…”

Several of his articles have been published in Ragazine and WorldView Magazines, Literary Yard, Literary Travelers and Quail BELL, while another appeared in “Crossing Class: The Invisible Wall” anthology published by Wising Up Press. His reviews have been published in the Midwest Book Review, by Revue Magazine, as well as Peace Corps Worldwide, and he has his own column in the “Arizona Authors Association” newsletter, “The Million Mile Walker Review: What We’re Reading and Why.” His essay, “Hugs not Walls: Returning the Children,” was a winner in the Arizona Authors Association literary competition 2020 and was reissued in “Revue Magazine.” Another article was recognized in the “Solas Literary Awards for Best Travel Writing.”

His honors include the “Service Above Self” award from Rotary International. He is a board member of “Advance Guatemala” and the membership chair for “Partnering for Peace.” His wife and three children were born in Guatemala. You can learn more at www.MillionMileWalker.com and www.Guatemalastory.net or follow him on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/millionmilewalker/