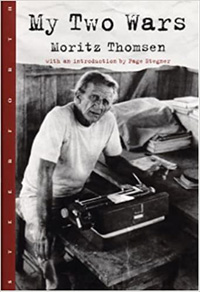

My Two Wars by Moritz Thomsen

Reviewed by

Mark D. Walker

This would be the last time we’d hear from “one of the best American writers of the century,” according to the Washington Post review of this book. Martha Gellhorn, Hemingway’s third wife and one of the best war correspondents adds, “wonderful sentences sound like a speaking voice, and the voice belongs to a man alone, a man both deeply grave and very funny, ironic and compassionate, totally honest, and without vanity.” As this book was completed shortly before his death and wouldn’t be published for four years after he’d past on.

This would be the last time we’d hear from “one of the best American writers of the century,” according to the Washington Post review of this book. Martha Gellhorn, Hemingway’s third wife and one of the best war correspondents adds, “wonderful sentences sound like a speaking voice, and the voice belongs to a man alone, a man both deeply grave and very funny, ironic and compassionate, totally honest, and without vanity.” As this book was completed shortly before his death and wouldn’t be published for four years after he’d past on.

Moritz lived as an expatriate for 28 years in Ecuador and chronicles his life in two extraordinary books. His first and best known book, Living Poor, is considered by the “grandfather of travel writing,” Paul Theroux, as one of the best Peace Corps chronicles ever. His second book, “The Farm on the River of Emeralds” tells the tale of meeting a local “zambo” or beach bum, Ramon, and establishing a farm on in an area you can only reach walking a long the beach in low tide. And after being thrown off that farm by Ramon, Moritz embarks on a journey through three countries in search for meaning to his life which becomes, The Saddest Pleasure: A Journey on Two Rivers.

In this book, Moritz describes the two great battles of his life—against a rich, tyrannical father and the other against German pilots and anti-aircraft gunners in the Second World War. . “Rarely has the similarity between war and family been as clearly drawn as it is in this scathing unblinking memoir,” said Kirkus Review.

Moritz’s relationship with his father was contentious and the conflicts surfaced throughout his life. As a child, his father’s cruelty would traumatize Moritz, as was the case when his father killed the house pet in front of the family because he’d killed some small chickens.

When his father learned his son had joined the Peace Corps, he called him a “communist radical” and disowned him. In one letter, Moritz reported that his father offered to buy him “a fucking one-way ticket to Russia. You make me sick. Your Loving Father.”

The meanness of his father comes to light at his funeral when according to Moritz, “My aunt, the youngest of my father’s sisters, and I were the only members of his family who were at his funeral. Everyone else was already dead or permanently estranged from him…” Moritz went on to say, “All in all, my father’s death had been a kind of gruesome slapstick comedy in which his madness had finally manifested itself publicly. His fortune to a bunch of yowling, pregnant pussy cats, for Christ’s sake? Ah, there’s many a slip twixt the cup and the lip.” He found it difficult to control the distain for his father, “I begin to write about him and find my body trembling with fifty year old angers. Old emotions still cramp my fingers; old injustices still march through my dreams.”

Moritz’s introduction into the military was most inauspicious, “I had not joined the army to get it over with and get out. Not at all. In 1940, I had been drafted—and so quickly after the draft laws were passed that I sometimes thought of myself as the first draftee and the draft laws as a plot promulgated for the sole purpose of screwing up my life.” He goes on to say, “…Smelling faintly of onions, pork grease, and potato peels, suddenly totally isolated from the idiotic rhythms of the soldier’s day, dressed in stained and sagging fatigues like a cartoon figure, crouched over a twenty-gallon pot or half hidden inside it, peeling spuds until my bleeding fingers stained their water, I sank into a placid and unthinking stupor that lasted for about nine months…”

After a grueling training program, he’d be assigned as a bombardier to the Eighth Air Force. But dropping bombs over enemy territory at night was traumatic in its own way, “…flying through that field of black flak over the target and watching the bombs flowering in the center of the city among blocks of buildings that were already rubble, I felt nothing but a dim sense of relief in getting rid of the bombs. What I was proudest of was simply that I had remembered at the proper moment to tighten my sphincter and deny my body its profound urge to void itself.”

And then there was the killing of innocent civilians which he reported, “…Ever since that day when the bombers had begun to explode and fall below our group, I had been furiously angry with that God whom I scarcely believed in. All that death, all that death. Why are You doing this to us? Why have You made us the way we are? Why, when life is so unspeakably foul, are we so terrified of being released from it?”

“Combat had twisted or robbed me of my better qualities, had made me touchy, cynical, secretive. I was too tired to work at putting together something with subtle complications—the advancing and retreating forays into the territory of another human soul” was Moritz’s summary of his war experience.

His commentary on the war evokes the poignancy and humor of Heller’s, Catch-22. Page Stegner, a fellow Returned Peace Corps Volunteer and writer would write the introduction to this book and say it was, “the best narrative account ever written of an imperfect and fragile human soul caught up in the air war over Germany.”

Moritz would never see his last book published. In January of 1991 his World War II pilot visited him in Guayaquil and returned to the U.S. with the manuscript of My Two Wars which he handed over to Moritz’s friend and fellow author Page Stegner who took a while to decipher it because Moritz had, “eschewed most forms of punctuation (in particular, the comma), and because he hadn’t changed the ribbon in his typewriter since Richard Nixon resigned from office..” He struggled to revise the manuscript based on Page’s critique and told him, “Page, I am half sick and will write you again in a few days.” Twelve days later he was dead.

His close friend and confidant, Mary Ellen Fieweger, who visited and supported him in his later years informed one of Moritz’s friends of his demise which was caused by cholera with, “He refused any and all treatment, including IVs, painkillers, and oxygen. I think he was ready to die, and determined to do it the way he had chosen to live most of his adult life. He died poor, with a disease that affects only the poor.”

Moritz received a number of literary awards, including the Paul Cowan Award in 1989, and the Washington State Book Award in 1991. His literary work has been recognized and exalted by writers such as Tom Miller, Martha Gellhorn and Wallace Stegner. Paul Theroux, a fellow Returned Peace Corps Volunteer and author of innumerable books, including The Mosquito Coast, gave Moritz a boost with a three-page cameo in his travel memoir, The Old Patagonia Express, portraying him as a father confessor. In this passage, Moritz implored Theroux to stop partying in Quito and get back to writing, which he did quite brilliantly.

Sixteen years after his death various people, including many local authors, celebrated his life with a conference in the capital city of Quito. Out of the conference came a 250-page “Virtual Magazine from the School of Liberal Arts of the University of San Francisco” in Quito with essays about Moritz written by other authors. The introduction of this magazine described Moritz as a “fascinating and peculiar” author of the 20th century—who wrote about Ecuador. He will be recognized as a significant 20th century figure for his life and his words and will be more fully appreciated posthumously.

Product details

⦁ Hardcover: 317 pages

⦁ Publisher: Steerforth; 1st edition (June 1, 1998)

⦁ Language: English

⦁ ISBN-10: 188364206X

⦁ ISBN-13: 978-1883642068

⦁ Product Dimensions: 6.4 x 1.3 x 9.3 inches

⦁ Shipping Weight: 1.5 pounds View shipping rates and policies

Reviewer Mark Walker was a Peace Corps Volunteer in Guatemala. After earning an MA in Latin American Studies from the University of Texas in Austin, Mark co-founded a Guatemalan development agency and then managed child sponsorship programs for Plan International in Guatemala, Colombia and Sierra Leone. He has held senior fundraising positions for several groups like CARE International, MAP International, Make A Wish International, and was the CEO of Hagar. Most recently, he completed a fundraising study for the National Peace Corps Association as a VP at Carlton & Co.

His involvement promoting “World Community Service” programs led to his receiving the most prestigious Service Above Self Award from the Rotary International Foundation, and all three of his children have participated in Rotary’s Youth Exchange program. His memoir, Different Latitudes: My Life in the Peace Corps and Beyond, won Honorable Mention in the Arizona Literary Award competition. He’s published various articles, including the featured article in the May 2018 issue of Revue Magazine, “The Making of the Kingdom of Mescal: An Adult Indian Fairy-Tale”; “The Fundraiser: Running risks in Nepal and Bolivia,” in the Spring issue of World View; “My Life in the Land of the Eternal Spring,” in the Fall issue of the “Crossing Class Anthology” published by Wising Up Press and an article by the same title as his book published in the Summer 2017 issue of Advancing Philanthropy. Mark’s wife and three children were born in Guatemala and now live in Scottsdale Arizona.